It wound up being just shy of a four-year wait to get to see the 2016 documentary Close Encounters with Vilmos Zsigmond. Basically, I had a movie poster for the Cannes selection long before I actually got to see it. But it was worth the wait.

Filmmaker Pierre Filmon starts his narrative deferentially, consulting with his subject matter on the different options that could be used to film the interview. What's notable about Zsigmond's reaction is he's not looking to intimidate the director. Vilmos is a master craftsman and the raison d'être for everyone being there, but he offers opinions instead of setting parameters. Also, he doesn't mind sitting on a film canister if it makes for a better shot.

So before the title sequence even rolls, we get a good idea of what Vilmos was like as a person and an artist, and thusly why so many in the business trusted him to get their jobs done.

Said title sequence is stunning, culling Zsigmond's opening credit from his pictures and cutting them together makes for an amazing pastiche -- McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, Deliverance, Sugarland Express, Obsession, Blow Out, The Witches of Eastwick, The Two Jakes, Maverick, The Crossing Guard and Black Dahlia. Whether or not these films wound up as box-office successes or critical darlings, they were visually superlative. Now all of them are -- at the very least -- cult favorites, and much of that has to do with Zsigmond.

The documentary doesn't just follow Vilmos around, it also chats up his collaborators and contemporaries. Pierre-William Glenn (Day for Night) points out that looking is a way to reflect and Zsigmond pushed him to question the way we look at people. Vilmos didn't just have a striking effect on us, he influenced those around him as well.

Dante Spinotti, who helped set some of the most distinctive moods in the '90s with the likes of L.A. Confidential and The Insider, calls Zsigmond an expert with light sources. Spinotti says the secret springs from the remarkable simplicity of his work and how the quality of his photography connects to the storyline. "He brought cinema forward," the two-time Academy Award nominee explained.

At this point in the movie, Vilmos talks about his humble beginnings in Hungary. At age 14, he didn't have any dreams. Then an uncle gave him a book about photography, and he realized the most component of that was light. In other words, the proverbial light bulb was turned on. Vittorio Storaro deems Zsigmond's work "traditional and elegant." And that's coming from a cinematographer who took home three Oscars for his work for Apocalypse Now, Reds and The Last Emperor.

But sometimes elegance needs to take a day off. At this point after all these glowing testimonials, Filmon shows the human side of his subject. During one interview session, Vilmos said he feels American. But then after taking in beautiful Budapest, he needs a bit of a rewind and an edit. No need for clear-cut definitions, he can change as the mood hits him. Would Zsigmond have become what he did without his start in Hungary, and the hours he spent poring over Italian movies? Ivan Passer (Cutter's Way, Stalin)

posits the significance of the Hungarian movement in 50s, followed by

the Czechs in 60s. Passer himself was a crucial cog in the latter.

John Boorman

(Deliverance and

Hope and Glory) makes sure the importance of Vilmos' departure from Hungary with fellow legend László Kovács in 1956 is not overlooked -- the duo documented the invasion by the Russians and fled with their treasured footage to Austria. "That's how we got to see that film," Boorman said. "The man who does that -- is that brave and that inventive -- I think he's exactly what I need in

Deliverance."

At one point, Zsigmond explains his affinity for black-and-white movies, how they're often more visual than films in color. He finds the poetry in the composition, by taking the light away from the light sources. Yet he doesn't consider himself much different from other cinematographers of his era -- Kovacs (Easy Rider, Ghostbusters and additional photography for Close Encounters of the Third Kind), Haskell Wexler (Oscar winner for Bound for Glory and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) and Owen Roizman (a five-time nominee for the likes of The French Connection and Network).

What Vilmos ultimately does concede is that many movies have been shot more beautifully than they might otherwise have been. Which is not to say that everything on the screen is always picture-perfect. "It should not look glorious," he said. "It's easy to make pretty images and then it ruins the movie." We get to see how much more comfortable Zsigmond is talking about the craft with compatriots such as Darius Khondji (Se7en, Oscar-nominated for Evita). Vilmos understands that digital photography makes the process faster, but sacrifices mood for speed. With five-time nominee Bruno Delbonnel (Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Inside Llewyn Davis) he points out the difference in approaches between Europeans and Americans.

It was very difficult for Zsigmond to make the transition when he emigrated to the United States. As in the also-fabulous No Subtitles Necessary, a documentary about Vilmos and László Kovács, he recalls the shock of coming to America and not knowing the language. Zsigmond was told point-blank to forget about his dream because he'd never make it. And ultimately his anger over that sentiment fueled his work as he worked hard to disprove it.

Vilmos' first movies with names like The Sadist and Blood of Ghastly Horror were gory and made on the cheap. This wound up being something of a godsend as he was credited as William Zsigmond. What he needed to do was get into the elitist American Society of Cinematographers, which was under contract to the big studios. "All my bad movies, they had the name William," he said. "They didn't have to recognize I was the same person."

Wexler was the one who changed everything for him. Vilmos considers him his mentor and the man who started his career in Hollywood. And then Peter Fonda paved the way for Zsigmond to use his real name in the industry on 1971's

The Hired Hand. Known on sets as "Ziggy," Fonda proclaimed he couldn't be both Bill and Ziggy, that his actual name should be on the credits.

And then the artist formerly known as Ziggy started settling in. One of his favorite places in the world is Big Sur, and Filmon spends time talking to his subject in a hot tub at place that became his home.

Vilmos' impact on the industry seemed immediate once he got to be himself again. Passer recalls McCabe and Mrs. Miller, noting he forgot the story but was entranced the look of the picture. It was the "expression of a vision of a cinematographer," he said. And he wasn't the only one, Delbonnel added that McCabe's director Robert Altman wanted authenticity and he found it in Zsigmond. Actor Michael Murphy (Nashville, Manhattan) and Khondji detailed the resistance risk-taker Altman faced from the union for the big studio picture. And with such techniques as flashing the film to expose it to light, the whole quality was changed for the better. "The studio freaked out," Khondji said. "They said it was unwatchable." But Vilmos worked with unconventional Altman again on The Long Goodbye. "I

loved it, I was so impressed by the fact he was a collaborator," he

said. "That's what made my career."

According to Boorman, casting the cameramen is just as important as the actors. He was impressed by Zsgimond's panning and moving shots on Deliverance. It required much fluidity to follow actors in canoes. "Like a mountain goat, he could get into any position with the camera -- up to his neck in water or crouching under a rock," Boorman said. "He was always pushing."

Zsigmond enjoyed working with good actors eager to improvise because that was similar to his own process. That worked well for Jerry Schatzberg on Scarecrow. He even got the director to change his mind on a crucial element of the feature. Because his characters (namely Gene Hackman and Al Pacino) were moving all the time, Schatzberg thought the characters should be. He recalls Vilmos listening to his thoughts, and after a while, thoughtfully pointing out he didn't see it the same way. The cinematographer saw it as more of a fairy tale and wanted to take beautiful pictures of America and put those two characters in it. "About 4 a.m., I convinced myself, that's the way it should go," Schatzberg said. "He's not just a photographer, he's a thinking photographer. You knew he read the script. He was into the script, he was into acting and he was into what the audience was going to think."

The documentary often references how well Zsigmond gets along with actors. A lot of it has to do with his style. By shooting in anamorphic frame, less cuts are required because he could hold on a two-shot for a very long time, enabling the performers to do their work while spotlighting the locations behind them.

That brings us to Steven Spielberg. Busy with other movies, Vilmos turned down the film that made Spielberg --

Jaws. He didn't like the story, preferring the scripts to the two movies he did make with Steven. They spent much of their down time on

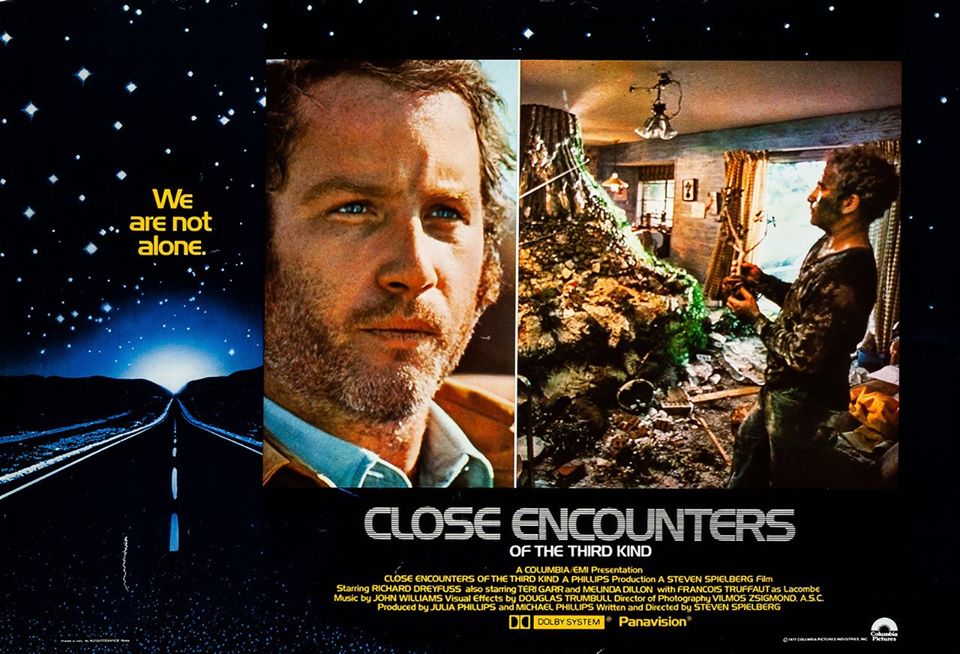

Sugarland Express talking about movies and style. We next see Zsgimond perusing his

Close Encounters of the Third Kind memorabilia. He looks at a program, actor Bob Balaban's published diary on the making of the movie, a poster and other assorted ephemera. Vilmos recalled how it started out with a budget of a "few thousand dollars" and kept becoming a bigger budget movie. When Richard Dreyfuss signed on as the star, the budget ballooned again. "(It) really got up at the end," he said.

In those days, there were many UFO sightings in America, which made the movie a hot property. And every night, Zsigmond remembered Steven coming up with new ideas while he was watching movies. On the verge of bankruptcy, Columbia Pictures was understandably concerned. "I keep telling them, don't worry about this, this movie is going to save Columbia," Vilmos said. The only concern Zsigmond had was for the final segment. They didn't have enough lights to make the last half-hour's fantasy sequence work, so his film was overexposed to heighten the effects of bright light.

All that care earned Vilmos the Oscar for Best Cinematography. The movie also picked up a special achievement Academy Award for sound effects editing and seven other nominations -- including a directorial one for Spielberg. Zsigmond still regrets forgetting to thank the director in his acceptance speech. "He deserved it," he said. "The whole movie was shot under terrible conditions."

Close Encounters brought Vilmos that ultimate recognition from the academy, but when it comes to people approaching Zsigmond, he says the movie they mention 95 percent of the time is his next flick --

The Deer Hunter. When a generator failed on set, Vilmos ended up filming with less light, which made the scenes feel more real and forced the audience to pay extra attention. "He's not afraid of enhancing the drama. He works in constant change," Delbonnel explained. "It's very difficult to do." Another Oscar nomination followed.

Over and over, the documentary points out Zsigmond's ability to deliver a coherent visual style, finding a balance in the aesthetics. Making sure the visual style is coherent. Two-time Oscar nominee Stephen Goldblatt (Batman Forever, The Prince of Tides) points out how honest his work depicts working-class stiffs being sent to die in a foreign country. "This was not a John Wayne war movie," Goldblatt said.

And after ascending to the highest heights, Vilmos tumbled back down with 1980's Heaven's Gate. The doc doesn't shy away from talking about it, pointing out that initially the movie was considered one of the biggest cinema disasters ever. That's turned around some in the ensuing years. "Nobody understood what it was about. America was in bad shape," Zsigmond said. "I think people understand this movie much better today." Isabelle Huppert recalls how Vilmos fueled the actors with his use of light. "We could feel it physically, sensually," she said. "He knew how to preserve moments in moments." For the actress, the shoot was a combination of intense moments of madness and pure inspiration.

Speaking of roller-coaster rides, wife Susan Roether Zsigmond went on a lot of them. It was difficult for her to grasp that his work always had to come first, but the pair traveled all over the world. For Passer's Stalin, they went to Moscow in 1991. In the midst of chaos, the crew stayed in Joseph Stalin's dacha and had access to Kremlin that had never been open to public.

It took some convincing for the director to get Zsigmond on board, though, since it was produced for HBO. As a joke, Passer told him, "You just single-handedly ruined the studio with Heaven's Gate. If you work with me, you will never stop working after Stalin." But it was true. And in that movie is one of Vilmos' most famous shots -- one that he only took three minutes to light -- of Stalin walking up the stairs with a shadow increasing behind him. "If you remember nothing else from the film, you remember that shot." Passer said.

Many of his collaborators experienced similar "wow" moments with Vilmos, like when Mark Rydell saw the nose of Bette Midler's plane coming into frame early in The Rose. On that shoot, Zgimond brought "the best of Hollywood" (including Kovacs and Wexler) in for the concert scene with license to shoot it anyway they wanted. That gave Rydell the enviable problem of not knowing which shot to use for his final cut.

John Travolta and Nancy Allen joined the documentary to talk about Blow Out, which Allen deemed the greatest shoot she'd ever been on. Vilmos chuckled about the bridge scene, filmed over the shoulder of a frog. It gets a little off the Zsigmond track, but Travolta makes a key point. "If you don't have confidence in your cinematographer, something in you dies," he said. "The right communication is in the framing and the lighting."

Vilmos got to be in front of the camera for a split-second while handling the cinematography on Richard Donner's

Maverick. "We needed a character to look like an old German artist, who better than Vilmos?" Donner questioned. "He came out in costume to set the shot. ... I love the way he worked. I love the look he gave movies. I loved the pleasure of working with him."

James Chressanthis, who went on to direct the aforementioned No Subtitles Necessary, found out how open Zsgimond was while working on The Witches of Eastwick. An intern at the time, he told Vilmos he saw a shadow on Michelle Pfeiffer during a scene. After looking it over in dailies, Zsigmond thanked him. "He was always very, very strong, powerful, had a point of view ... at the same time, he was very, very humble and generous and accepting of suggestions," Chressanthis said. "He was strong and flexible and inclusive ... so crews loved him."

Late in his career, Vilmos handled the cinematography chores on several Woody Allen movies, Melinda and Melinda, Cassandra's Dream and You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger. His affinity for longer takes matched up well with the actor/director's style. "He decided to have someone else, and I was the someone else," Zsigmond said. And with his career encapsulated as on the celluloid he loves, Hollywood's go-to someone else is free to walk off into the distance with his back to the camera.

Not that we needed a reminder, but Close Encounters with Vilmos Zsigmond, currently only available on DVD in PAL format, gives us a peek at the creativity behind the lens that was so essential to Close Encounters of the Third Kind. --Paige

Comments

Post a Comment